How to Organise your Journeys for Effective Decision Making

Introducing the A.V.O.C. framework.

Are you drowning in a sea of journeys, unsure how they relate to each other, and unclear about what to prioritise? Thinking of transferring them to a journey management system but not sure where to start? If this resonates with you, keep reading. I have a solution for you.

In this post I’m introducing the A.V.O.C. framework. To some, it may sound like a dancing avocado, to others, like widespread destruction. It's neither – or perhaps a bit of both. I developed this framework after over 15 years of working with large organisations, structuring their journeys, services, and products for more effective and informed decision-making.

You're after better-informed decisions that benefit both the business and clients, right? A journey is a tool, a simplistic representation of reality, not an outcome in itself. It's an output, a means to an end. Without an effective framework, it can be pretty useless.

A.V.O.C. stands for: Anchor, Variations, Outcomes, and Change.

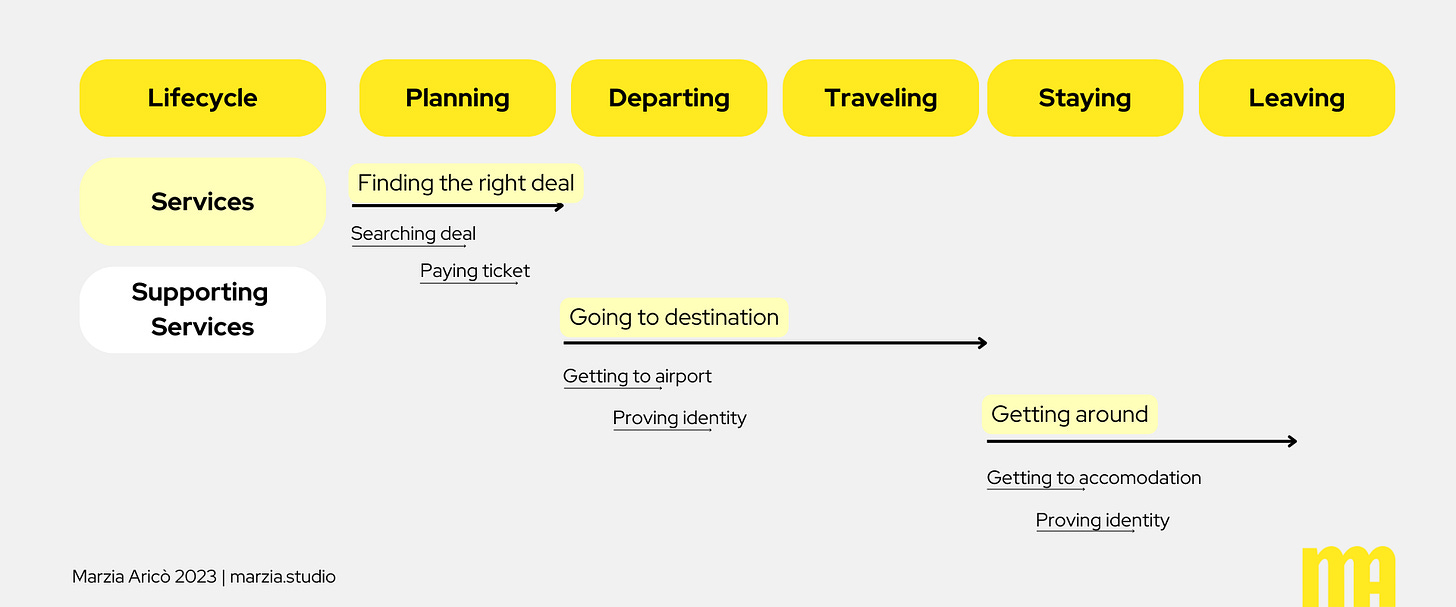

Anchor: This is what hardly changes, holding everything else in place. It includes: Lifecycle, Services, and Supporting Services.

Variations: The part that always changes, encompassing all the ways people experience your services: Products, Journeys, and Blueprints.

Outcomes: The elements that guide decision-making. This allows you to measure how you are performing, assess, and recalibrate. It includes: Desired Outcomes for Clients, Business, Operations, and the Environment, as well as Indicators, and Metrics.

Change: The rules of how change happens in your organisation. This encompasses prioritisation mechanisms and operating model.

In this blog post, I will detail how to organise your journeys for success. But first, let's align on some foundational concepts: the definitions of product, service, and journey. I've defined these in a separate blog post on service essentials, but here's a summary:

Services: The way an organisation allows someone to do something they need to do. Example: I need to travel from Amsterdam to Rome for work. The airline KLM facilitates this. My need (reaching Rome) aligns with their goal (making money by moving people around).

Products: Enablers of service provision, either physical or digital. Without a product, a customer can't access a service. Example: The website I used to book my ticket to Rome; The app I used to check in; The aeroplane I flew in.

Journeys: The way someone goes about experiencing the services and products. The journey unfolds regardless of whether an organisation has intentionally designed it. Example: On this occasion, I am a business traveller, opting for light luggage, and a short stay. I expect everything to run smoothly and punctually, with no unexpected delays. I'll mostly engage with the service digitally until I board the plane.

Now that we are aligned on the foundations, let's dive into the constituent parts of the framework.

Anchor: The Bit That Hardly Changes

Businesses are in a state of constant flux. Their offers, strategies, and organisational structures change (shall we talk about the umpteenth restructuring you're currently undergoing?). Therefore, the anchor, the bit that hardly changes, cannot be found internally. It must be found externally, with your consumers – people or businesses who have needs to be met by organisations in your sector (this is true both for B2C and B2B).

The anchor is your consumer lifecycle. This outside-in approach takes the perspective of the person or business with a need. It applies to any organisation in your sector, including yours. This view is relatively stable, changing only with significant market shifts, which fortunately don't occur every quarter.

The task might seem straightforward, but it's far from it. It's crucial to get this right, as errors and biases here will permeate the entire framework. Base your understanding on real research with real people. Collaborate with colleagues from other organisations in your sector since you're all navigating the same lifecycle.

Your lifecycle acts as the anchor for your service list – and I deliberately use the term 'list'. Start by compiling all the services your organisation provides (you can find tips on this in the service essentials blog post). Then, assign each service to the appropriate stage in the lifecycle, considering the needs each service supports and at which lifecycle stage these needs are relevant.

Each primary service will be supported by 'supporting services'. These include tasks like 'paying', 'registering information', or 'setting up something'. They are transactional in nature. You can think of these as second order services, often relevant to multiple first order services. For example, the act of paying may be involved in several services you offer. These second order services can also be thought of as 'service patterns'. Define and design them once, then apply them as needed to ensure consistency throughout the lifecycle.

Your anchor will look something like the example below.

Variations: The Part That Always Changes

The anchor's purpose is to hold in place those elements that frequently change: your products, journeys, backend processes, policies, and systems critical to service delivery.

This approach allows your products to be seen in context, which is a radical shift for many organisations. Products are often developed in isolation. As organisations are commonly structured around their products, a product often becomes a standalone line of business. Positioning products within the A.V.O.C framework enables you to view them in the context of the client. You can now understand how a product supports a specific service and how it intersects with other products and services. Magic.

Suddenly, a product team has a map showing what other product teams are doing and how their work intersects. Your map will look high-level like the example below.

This is the moment where journeys come into play. Let's pause to note that we didn't start with journeys. There's substantial groundwork required before we can safely begin to understand and position our journeys. Journeys are a part of the framework; they are not the framework itself.

As outlined in my service essentials glossary, journeys describe how someone experiences the services and products. You'll likely identify several key journeys for each service, each tailored to the needs of a specific client group. These needs should be grounded in both qualitative and quantitative research, not based on an internal assumption of what that group requires.

Imagine being able to expand (or double-click) on each service and visualise all of the different journeys clients can go through to experience that specific service. Journeys are connected to a service blueprint, detailing the client's experience and what the organisation must do to deliver it. Here you'll find specifics of all your processes, policies, and systems that bring the service to life.

The content in this section is subject to frequent changes. Therefore, it should be a living document, continuously updated to reflect changes and how each element affects the others. This dynamic nature is why journey management tools are now indispensable for organisations.

Outcomes: The Reason Why You Choose to Do What You Do

“What are you here to do as an organisation?” That’s the first question I usually ask my clients. Getting a unified answer from a team within the same company is rare. The question is simpler to answer in smaller organisations where the distance between employees and the people they are there to serve is relatively short. However, when you start growing, employing tens of thousands of people, as many of the organisations I've worked with do, the distance between the average employee and the people they serve becomes really wide. Everyone begins to focus on a section of the story, losing sight of the overall picture.

"What are we here to do?" is probably the most powerful question one can ask in an organisation. This part of the framework helps guide people towards an answer that is understandable, shared, and measurable.

Before we dive in, I’d like to clarify the difference between outcomes and outputs. These terms are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings and their difference is crucial in this context.

An output is the direct result of a process or activity. It's usually a tangible 'thing'. For example, in a manufacturing plant, the output could be the number of cars produced in a day. An outcome, on the other hand, is the final effect or result achieved over time. It encompasses the broader impact or changes brought about by the output, usually representing a new state of affairs. For example, in the context of the manufacturing plant, the outcome might be increased market share or customer satisfaction due to the quality of the cars produced.

In summary, an output is about the immediate products or results of an activity, whereas an outcome is about the long-term effects or impacts of those outputs.

The A.V.O.C. framework guides you to define the outcomes you aim to achieve for four key actors:

Clients: What are you aiming to achieve for the people (or businesses) you serve?

Business: What are you here to achieve for the business?

Operations: What do you aim to achieve in terms of operations for service delivery?

Environment: What do you want to achieve in terms of your impact on the natural environment?

You need to determine these outcomes collectively, involving individuals from across the organisation. Write these outcomes in plain language, understandable to everyone, regardless of their position. Aim for a few outcomes per section, ideally no more than three. This exercise forces you to prioritise what truly matters.

Next, identify indicators for each outcome. These are signals showing whether you are close to achieving your outcomes. Indicators are often qualitative. For example, if one of your outcomes for clients is 'I want to decrease the amount of time spent on check-ins,' an indicator signalling that the service is delivering this outcome could be 'Check-in data are pre-filled.'

Then, attach a metric to each indicator, ideally one or two metrics per outcome. Metrics are usually quantitative. In our example, a metric could be 'Time spent on check-ins.' You'll end up with a handful of metrics to monitor your business's performance. Knowing what you are there to do simplifies everything – all the other countless metrics you were monitoring before become just noise.

Change: The Rules of How Change Happens in Your Organisation

By now, you have a clear view of the services you offer, how your products support these services, and how your journeys unfold. You understand what you are there to achieve and how you're performing against your defined outcomes. You're fully aware of the status quo and are now ready to use this knowledge to drive meaningful change.

Why do I call it meaningful? Because you now know where you are and where you want to go. Every step should be deliberately chosen to bring you closer to the future you envision. I've often witnessed erratic decision-making based on hunches rather than data, where the loudest voice prevails, often leading to disastrous results for the business, clients, employees, and the environment. This can be termed 'failing leadership'. The framework provides leaders with the necessary context awareness and a sense of shared direction.

The final part of the framework determines 'how change happens around here.' The first element addresses how priorities are set. This aspect of the framework should naturally emerge from your outcomes. The outcomes you've selected form the backbone of your prioritisation mechanism. Collectively, you'll need to choose two or three outcomes to focus on at any given time to move closer to your desired future. A dedicated forum is needed for this, where a diverse group of business representatives can discuss and negotiate these priorities. The mechanics and results of this process must be transparent to the rest of the organisation.

This leads to the determination of an operating model that makes everything discussed so far become business as usual. The A.V.O.C. model becomes the standard approach to change in your organisation. This stage of the process might lead you to rethink your organisational structure and related roles. For example, many organisations I've worked with have felt the need to reorient around services rather than products, leading to the emergence of roles like a service owner who collaborates with various product owners to ensure a comprehensive view of the work.

Both prioritisation mechanisms and the operating model require a high degree of openness to experimentation. These forums, guidelines, and routines need to be prototyped through action and learning, iterating into forms that work best for your specific organisation and context. There is no one-size-fits-all blueprint for this. These structures are highly contextual and require intentional engagement from all relevant stakeholders.

Congratulations, you have now changed the way your organisation approaches change. It doesn't get more meta than this.

The A.V.O.C. Cheat Sheet

If you've read up to this point, you deserve a little perk. I have put together a cheat sheet for you and your team to start this journey.

Should you find this useful, I have designed a short series of five workshops to help you set up your framework. At the end of these sessions, your team will be equipped with a framework to organise CX initiatives and transformation. You don’t need to invest hundreds of thousands of €$£¥ to achieve the right setup. What you need is the right team, this framework, and a little guidance to structure your start correctly. Contact me at x@marzia.studio if you’d like my support. It's easier than you think.

If you've found this post insightful, I would truly appreciate it if you could share it with your network on LinkedIn. By doing so, you'll join the secret society of good people sharing awesome content. You can find me on LinkedIn by following this link.

thanks marzia, I like the clear overview and definitions you give:) It resonates with my view (and also what I teach at TUDelft) on Journey Mapping (purposely a verb, not a thing). Decide why you want to develop and use journeys; is it for (1) understanding the user experience better (empathic insight), (2) for ideation, (3) decision making (add metrics), or (4) engaging others in the service design process.

Hi Marzia I could connect how jobs-to-be-done can be the Anchor. Jobs are valid over time, solution agnostic and differing circumstances dictate the need for various journeys.

What’s great about AVOC is how it breaks silos across service design, product management and customer experience design. It shows all everyone can play together.

Thank you so much for sharing this framework :)